Beaver Valley becomes data center target

Beaver Valley becomes data center target

Local leaders are weighing the hopes of future tax revenue and economic development against the small arsenal of tools they have to inform and protect residents

Early last year, Rich Urick drafted his first data center ordinance for Shippingport, a Beaver County borough with about 160 residents and a storied history of big things happening.

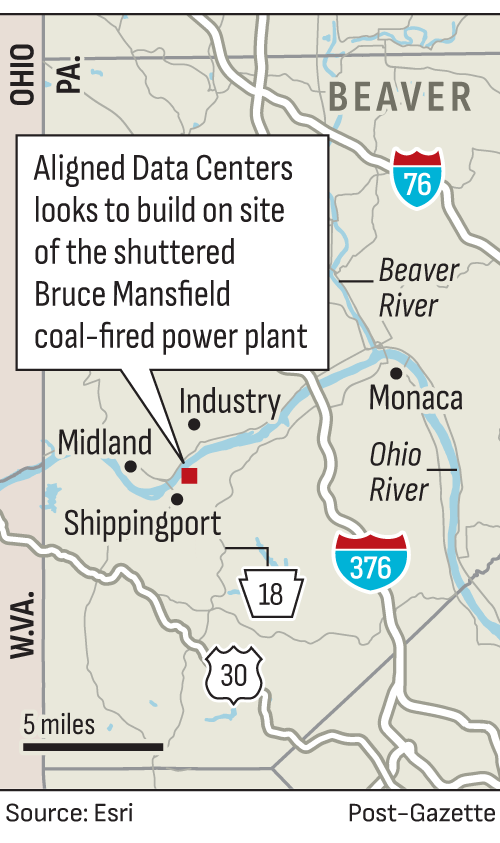

This was months before Mr. Urick, the borough’s solicitor, would learn about Aligned Data Centers’ plan to build a massive data center campus next to the shuttered Bruce Mansfield coal power station.

Borough leaders didn’t know the Texas-based developer was coming, he said — but they knew something was.

“Having an ear to the ground and seeing what’s happening in different parts of the country,” Mr. Urick said, “and here (we are), where there are two power plants, one operating and one not. … We just kind of wanted to get a jump on things.”

The operating plant is the Beaver Valley Power Station. And the plant is already tied into the data center universe. Last month its owner, Vistra Corp., signed a 20-year deal with Meta to offset the power demand from the tech giant’s data centers with electricity from Vistra’s nuclear plants, including Beaver Valley.

The defunct facility that Mr. Urick referenced is the Bruce Mansfield plant, which huffed its last coal-dusted breath in 2019 and was bought by Frontier Group of Companies in 2022.

Frontier cleared the coal piles, renamed the area Shippingport Industrial Park and began marketing its ground to data centers and large industrial clients. It plans to turn Bruce Mansfield into a natural gas power plant in the future.

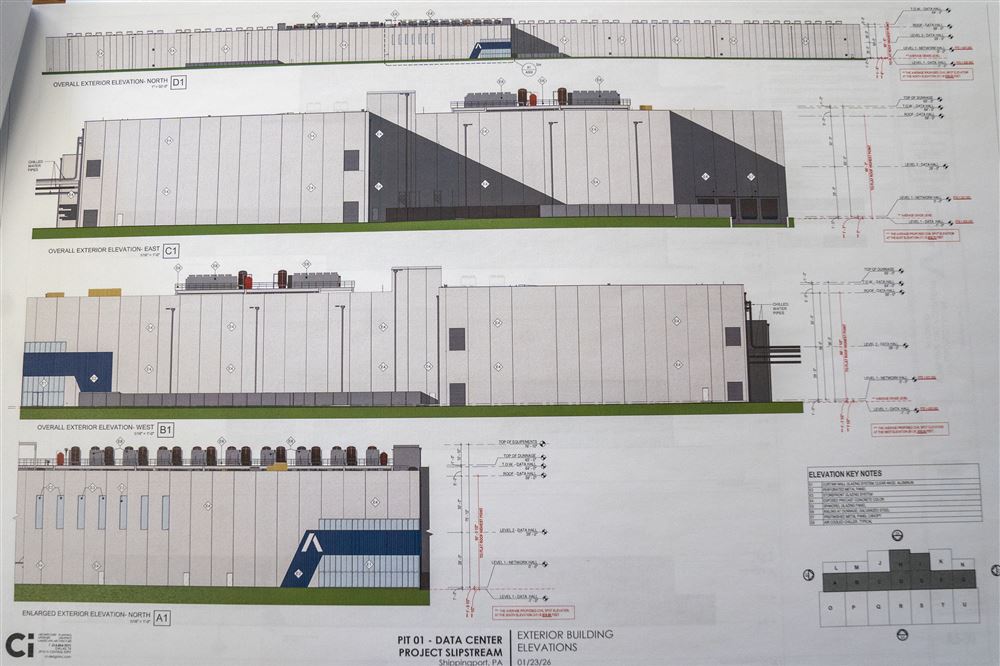

Shippingport’s data center ordinance, which passed in March, got its first test last month, when borough council approved Aligned’s plan to build up to three data center buildings, totaling 2 million square feet. The plan, which Aligned has dubbed Project Phoenix, also includes its own natural gas power plant that will be built to serve the data centers.

“Our goal is to be a great neighbor for years to come,” Aligned’s executive vice president of brand strategy, Joanna Soucy, said in an email. “If this project moves forward, we look forward to bringing high-quality jobs and significant economic opportunities to the area.”

Positioned for growth

Aligned told local officials that it is working to secure a customer for its data centers. The developer also hasn’t bought the land from Frontier yet.

As one economic development official put it, this isn’t a done deal.

But it is a serious one.

Of all the proposed data center projects in Western Pennsylvania, “that’s probably the one that’s moved furthest along right now,” said Dan Diorio, vice president of state policy for the Data Center Coalition, an industry advocacy group.

But there are other stirrings in the Beaver Valley. An outfit called Fezzik Energy that counts land developer Chuck Betters, attorney Jonathan Kamin, and Joanna Doven as partners is working to attract data centers to former J&L Steel sites in Midland and Aliquippa.

Midland sits right across the Ohio River from Vistra’s Beaver Valley plant.

In August, a Vistra subsidiary bought a 74-acre farm in Hookstown, a mile from the boundary of Beaver Valley, for $4.2 million — more than 10 times its assessed value.

A Vistra spokeswoman, Meranda Cohn, declined to say what the company has planned for the parcel, but offered this: “We often expand the footprint of our real estate around our plants in order to position ourselves for growth, so that when the right opportunity comes along, we can move quickly — whether that opportunity is with a particular customer, expanding operations, or investing in next-generation advanced nuclear.”

As Aligned CEO Andrew Schaap put it in a recent article he wrote for Forbes.com, “One resource that isn’t in short supply: capital.”

“Funding is rapidly flowing into the industry,” he wrote, using his company as an example.

In October, Aligned was acquired by BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, with other investors that include chip maker Nvidia, Elon Musk’s xAI and Microsoft. The deal was valued at $40 billion.

Community engagement

Big names and hefty price tags not withstanding, news of the Aligned data center project came to Shippingport residents indirectly, when some received a notice about seismic testing to ensure their foundations weren’t impacted by blasting activity at the industrial park.

What blasting activity, they wondered. Borough officials wondered the same thing.

“Someone jumped the gun,” said Pat Lampe, Shippingport’s emergency services coordinator.

By Dec. 5, Aligned had filed a conditional use application with details of the project, and a few days later, at the borough’s public meeting, a company representative apologized for the confusion.

Mr. Urick, the solicitor, “emphasized that the project should proceed at a slower pace to allow proper review,” the meeting minutes said. In September, Mr. Urick showed his frustration with Frontier, the site developer, for “the lack of transparency shown by the company throughout the project.”

Frontier’s representative, Anthony Basil, apologized at that September meeting. He said Frontier was trying to navigate the “many moving parts and multiple interested parties, which has made it challenging to keep everyone fully informed as developments occur.”

Mr. Basil has declined interview requests from the Post-Gazette and most recently suggested that questions should go through Aligned.

The data center developer responded with a statement, but declined to answer questions beyond that.

Kept in the dark?

Shippingport is no stranger to industrial activity.

But like many small towns that find themselves potential data center hosts, it is weighing the hopes of future tax revenue and economic development against the small arsenal of tools at its disposal to inform and protect its residents.

As is common for data centers and other industries scoping out potential projects, local officials are sometimes asked to sign non-disclosure agreements, which typically mean they can’t publicly discuss these projects until public notice is filed.

“Too many of these projects have been shrouded in secrecy, with local communities left in the dark about who is coming in and what they’re building,” Gov. Josh Shapiro said during his budget address last week. “Developers must commit to strict transparency standards and direct community engagement.”

Companies that live up to these standards bring their own power, hire and train local labor and sign community benefit agreements, Mr. Shapiro said, are promised “speed and certainty in permitting and available tax credits.”

With data centers as the economic engine du-jour, companies and municipalities are cautious about jeopardizing real opportunities by speaking too soon, while at the same time looking for some attention to put themselves on the map.

“In the beginning, you’re cloak and dagger,” said Dwan Walker, mayor of Aliquippa and borough manager at Midland, who is eager to see old industrial graveyards reborn, perhaps as data centers.

“You don’t want want to speak a blessing in the air because someone might snatch it,” his grandmother used to say. But as soon as something gets out, people wonder why they hadn’t heard about it before. “It’s a catch-22,” he said.

Community groups have sprung up to oppose proposed data centers, driven in part by concerns about noise and environmental impacts, but also by the feeling of being kept in the dark.

In December, as Springdale Borough Council voted, 5-2, to approve a conditional use permit to convert the former Cheswick Generating Station into a data center, the space was packed and each vote of yes or no brought an uproar from residents.

In Shippingport, a far smaller and much less rowdy crowd showed up for Aligned’s first information meeting in December, where the company flipped through a long slide show with renderings of long silver buildings.

Much-needed dollars

Ms. Lampe, the emergency services coordinator, was in the crowd, as were residents from nearby townships such as Potter and Raccoon. They came to learn, she said.

“A lot of people don’t know what a data center is — even though they have shown pictures, and they’ve explained (it) — some people, they’re not picturing it,” she said.

Some wondered how the development would impact their property values, she said. Others worried about landslides and stability issues in a hilly area that sits on top of mines.

One woman said she planned to live the rest of her life in the area, Ms. Lampe recalled. “She just wanted to know nothing was going to change.”

Tim Goughnour, a Shippingport resident, said last week that a new project could bring in some much-needed dollars.

“We’ve lost so much revenue, we haven’t been able to really care for the borough in the way we should have been able to all these years since … the loss of revenue from Bruce Mansfield,” he said. “So I think everybody’s looking forward to what’s going to come of this.”

Mr. Goughnour’s mother-in-law lives in a house right up against Bruce Mansfield’s property line, “and she’s been watching them dig out the giant dirt pile that they put in that parking lot.”

Rolling out the red carpet

One way or another, residents piece together what’s going on in their townships.

“If you put your ear to your own wall, you can hear all your neighbor’s business,” Mr. Goughnour said. “That’s how tight this community is.”

Constructing a data center is, and should be, a community effort, said Ms. Doven, executive director of the Pittsburgh-based AI Strike Team.

“There’s a natural process that takes place around community engagement, because data centers are a new-use case in many scenarios, so you have to change zoning,” she said.

For a project in Midland that she said is similar in scale to Aligned’s Shippingport plan, Ms. Doven said she’s been in frequent contact with borough council and the mayor, and they’ve had many questions.

“There’s many local communities and there’s many commissioners that are rolling out the red carpet for these investments,” Ms. Doven said. “It's up to local communities and commissioners to decide, A, if they have the the aligned assets, and then, B, if this is an investment that they want.”

She added: “Former industrial sites abound in Beaver County.”

First Published: February 8, 2026, 4:00 a.m.

Updated: February 9, 2026, 11:47 a.m.

- Log in to post comments