The dangerous business of dismantling America’s aging nuclear plants

By Douglas MacMillan May 13, 2022 at 6:55 a.m. EDT

By Douglas MacMillan May 13, 2022 at 6:55 a.m. EDT

All three incidents occurred on the watch of Holtec International, a nuclear equipment manufacturer based in Jupiter, Fla. Though the company until recently had little experience shutting down nuclear plants, Holtec has emerged as a leader in nuclear cleanup, a burgeoning field riding an expected wave of closures as licenses expire for the nation’s aging nuclear fleet.

Over the past three years, Holtec has purchased three plants in three states and expects to finalize a fourth this summer. The company is seeking to profitably dismantle them by replacing hundreds of veteran plant workers with smaller, less-costly crews of contractors and eliminating emergency planning measures, documents and interviews show. While no one has been seriously injured at Oyster Creek, the missteps are spurring calls for stronger government oversight of the entire cleanup industry.

Workers walk past the site of a building demolition at Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station in New Jersey. Regulators have documented at least nine violations of federal rules at the plant under Holtec’s ownership. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

In the nearly three years Holtec has owned Oyster Creek, regulators have documented at least nine violations of federal rules, including the contaminated water mishap, falsified weapons inspection reports and other unspecified security lapses. That’s at least as many as were found over the preceding 10 years at the plant, when it was owned by Exelon, one of the nation’s largest utility companies, according to The Post’s review of regulatory records.

Joseph Delmar, a spokesman for Holtec, defended the company’s record, saying it takes safety and security seriously. The recent incidents “are not reflective of the organization’s culture,” he said, adding that the worker who knocked down the power line “did not follow the proper safety protocols.” Delmar said the company has decades of experience building equipment to store nuclear waste and employs veteran plant workers to dismantle reactor sites.

“While the decommissioning organization may seem new, the professionals staffing the company are experienced nuclear professionals with intimate knowledge of the plants they work at,” Delmar said in an emailed statement.

Analysis: Who's afraid of nuclear power?

Holtec is, however, pioneering an experimental new business model. During the lifetime of America’s 133 nuclear reactors, ratepayers paid small fees on their monthly energy bills to fill decommissioning trust funds, intended to cover the eventual cost of deconstructing the plants. Trust funds for the country’s 94 operating and 14 nonoperating nuclear reactors now total about $86 billion, according to Callan, a San Francisco-based investment consulting firm.

After a reactor is dismantled and its site cleared, some of these trust funds must return any money left over to ratepayers. But others permit cleanup companies to keep any surplus as profit — creating incentives to cut costs at sites that house some of the most dangerous materials on the planet.

Even after reactors are shut down, long metal rods containing radioactive pellets — known as spent fuel — are stored steps away, in cooling pools and steel-and-concrete casks. Nuclear safety experts say that an industrial accident or a terrorist attack at any of these sites could result in a radiological release with severe impacts to workers and nearby residents, as well as to the environment.

Holtec International opened the 50-acre Krishna P. Singh Technology Campus in Camden, N.J., in 2017. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the independent federal agency tasked with overseeing safety at nuclear sites, conducts regular inspections during the decommissioning process. But state and local officials say the NRC has failed to safeguard the public from risks at shut-down plants, deferring too readily to companies like Holtec.

“The NRC is not doing their job,” said Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.), who has pushed the agency to adopt stricter regulations around plant decommissioning. “We need a guaranteed system that prioritizes communities and safety, and we don’t have that right now.”

The NRC’s leadership is divided over the role regulators should play. The agency was created in 1974, as the first generation of commercial reactors was going online, and its rules were mainly designed to safeguard the operation of active plants and nuclear-material sites. As reactors shut down, the NRC began reducing inspections and exempting plants from safety and security rules.

Last November, the NRC approved a new rule that would automatically qualify shut-down plants for looser safety and security restrictions. Christopher T. Hanson, a Democrat nominated by President Donald Trump and promoted to the role of chairman by President Biden, has said the changes would improve the “effectiveness and efficiency” of the decommissioning process.

What Should America Do With Its Nuclear Waste?

Commissioner Jeff Baran, also a Democrat, voted against the proposed rule and called for the NRC and local governments to play a bigger role. “Radiological risks remain at shutdown nuclear plants that must be taken seriously,” he cautioned in public comments. Baran added that the agency already takes a “laissez-faire” approach to decommissioning and that the new rule “would make the situation even worse, further skewing the regulation towards the interests of industry.”

Dan Dorman, the NRC’s executive director for operations, said in an email that the agency lifts restrictions at plants only if it determines the plant will continue to be safe. In addition to citing Holtec for violations at Oyster Creek, the agency has required the company to take corrective measures, including external security assessments of all its nuclear sites.

“Our increased oversight and the recent enforcement actions demonstrate our concern about the situation at Oyster Creek,” Dorman said.

The emissions stack at Oyster Creek, which was permanently shut down in 2018. The plant’s single reactor generated enough electricity to power 600,000 homes. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

Holtec faces mounting criticism beyond Oyster Creek. Michigan officials have said they worry Holtec will leave residents on the hook for cleanup costs at the Palisades plant on the shores of Lake Michigan. Massachusetts officials have protested Holtec’s plan to take 1 million gallons of contaminated water from the defunct Pilgrim power plant and dump it into Cape Cod Bay.

While Holtec acknowledges a funding shortfall at Palisades, Delmar says the fund will appreciate in value to cover the cost of the cleanup. At Pilgrim, Holtec has said the potential radiation dose from the Cape Cod release would be far less than the average traveler receives on a typical cross-country flight.

In the Southwest, Holtec has ignited a different controversy. As the company acquires old plants, it is proposing to ship the highly radioactive spent fuel to New Mexico, where it plans to build a storage facility. Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham (D) has vowed to fight the plan, telling Trump in a 2020 letter that storing radioactive material in the oil-rich Permian Basin region would be “economic malpractice.”

Holtec says it is working in partnership with a group of local officials who believe the benefits of the facility — including new jobs and investment — outweigh the risks. On its website, Holtec says the facility will provide “a safe, secure, temporary, retrievable, and centralized facility for storage of used nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste until such time that a permanent solution is available.”

The growing debate marks the latest twist in the tortured saga of nuclear power, which once was hailed as a miracle technology capable of producing large quantities of clean, affordable energy. In the early 1970s, the federal Atomic Energy Commission estimated that about 1,000 reactors would be built in the United States, and that nuclear sources eventually would provide at least half of the world’s power.

But those ambitions soon collided with fears about nuclear radiation, especially after disastrous meltdowns at Chernobyl in Ukraine and Fukushima in Japan. Nuclear energy peaked at around 18 percent of global electricity production in the 1990s and now comprises about 10 percent, according to the U.S. Energy Information Association.

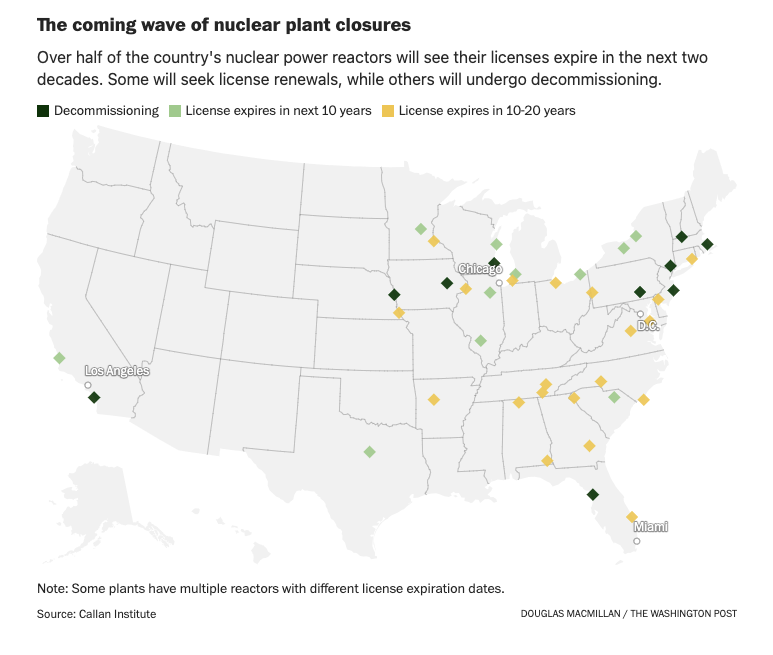

Reactors in the United States initially were licensed for 40 years, and most were renewed for another 20 years. Of 94 reactors that are still active, licenses at over half are set to expire in the next two decades, according to Julia Moriarty, a senior vice president at Callan.

Recently, worries about climate change have led some governments to embrace nuclear as a low-carbon source of power. Biden has called nuclear essential to the nation’s climate goals, and Washington last year set aside $6 billion for extending the licenses of some plants and $2.5 billion for developing new nuclear technologies.

But the nation continues to puzzle over the problem of nuclear waste. This material, which emanates invisible but harmful radiation for hundreds of years, is stored in protective containers on the grounds of nuclear plants, scattered in dozens of towns across the country. A plan to build a national waste repository in Nevada’s Yucca Mountain stalled amid decades of political gridlock, leaving these towns saddled indefinitely with the threat of an accidental release or terrorist attack.

Holtec is approaching those communities with an offer to clean up the mess.

- Log in to post comments